Book review by Rebecca Barnes |

Book review by Rebecca Barnes |

T. Wilson Dickinson has published an excellent book that will be of great importance to the church at large and the ecumenical movement for economic and environmental justice. It will be invigorating to individuals and congregations. As a professor at Lexington Theological Seminary in Kentucky and as a writer, pastor, organizer, Dickinson has created a clear, thought-provoking and hopeful book that is indeed “good news.”

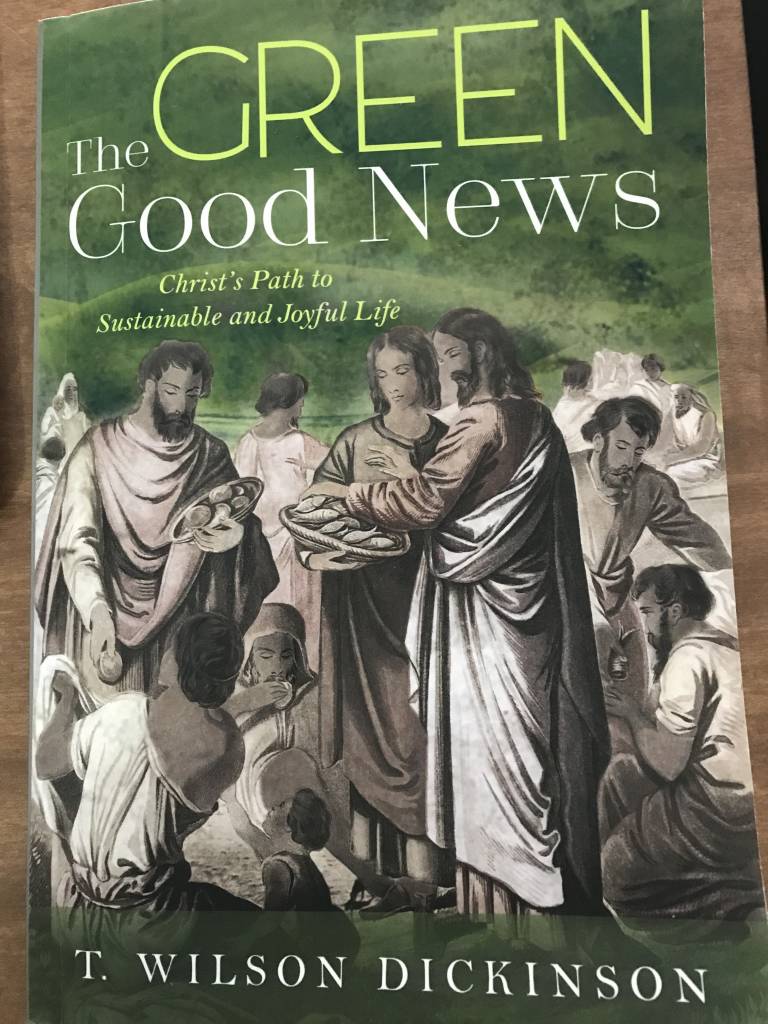

“The Green Good News: Christ’s Path to Sustainable and Joyful Life” (2019) explores how Jesus encouraged, challenged, and shared ways for us to create sustainable, holistic, and joyful communities where healing, nourishment, and justice are available for all.

Photo courtesy of Second Presbyterian Church, Giddings-Lovejoy presbytery

This is the kind of theological and scriptural study we need in our time. While living in the midst of a global pandemic, rampant racism, famines in multiple countries, and many people feeling isolated or alienated, the hope and joy of this book paint a different way of being, a new way we need as much as Jesus’ first disciples did. Dickinson’s thoughtful explorations of Jesus’ words and parables invite us into working towards a healed and inclusive community that is radically just.

Near the beginning of the book, Dickinson writes that “the cross marks the dual movement of both resisting the injustice of the Empire, and living a life entirely dedicated to love regardless of the cost” (p. 13). He argues that “Jesus was anointed to proclaim good news to the poor, to release the oppressed from structures of empire for ways of delight, love and justice,” (p. 24) and that “if we can see Christ as the servant anointed for this task, then we can also hear the call to follow his path of servanthood and love for the renewal of all creation” (p. 25).

The joyful good news is that this path offers profound grace to all of us, regardless of where we fall on the spectrum of oppressor and oppressed. While we are all trapped in systems that divide us—wealthy and poor, landowner and worker, racially privileged and racially oppressed—Christ invites us to break through these systems of injustice and empire, into a new way of love.

I was intrigued by Dickinson’s explorations of gardens, land, and agriculture in the bible—from the garden of Eden to the garden of Gethsemane to talking about Herod’s food economy. Dickinson uncovers these stories for critical implications of our modern-day food systems and how we should care for God’s creation and one another. He creates a compelling biblical case for food justice as he critiques some ways that our current farm-food system “obscures the ways that wealth is extracted from the fertility of the land and the labor of workers, who are now portrayed as the recipients of charity” (p. 75).

He also explores debt, the imperial economy and links to our economic systems today that keep people trapped. He writes that “Jesus’ promise is not that the poor shall become rich, because the logic of wealth is at the root of the problem” (p. 59). Thus, the reversals that Jesus taught in many parables challenge our thinking about what our goals are and what our achievements should be as human beings in this society. Often, the divine desire for us is surprising and unexpected and at complete odds with what culture and empire have taught. For example, “The reversal of the order of the wealthy does not idealize poverty and the poor and leave the only authentic followers of Jesus as itinerate individuals who have no possessions. The covenantal renewal and transformation at the heart of his ministry points towards an alternative vision of equitable, sustainable, and joyful communal life” (p. 61).

By providing attention to historical context, Dickinson helps us to understand how radical and transformative some of Jesus’ actions were and asks what would modern equivalents be, if we were to follow Christ. He writes that the “wilderness feeding was a direct challenge to the imperial system and way of life. Simply gathering 5,000 people was considered sedition in the Empire and was punishable by crucifixion” (p. 81). Dickinson shares that Jesus’ acts of healing and wholeness were about physical as well as social bodies and also about community—not just individual—healing. Can we do the same? Whether it’s the story of feeding the 5,000, the Last Supper, or our modern experiences of sharing meals, Dickinson writes that the practice of breaking bread together can help us to set “our eyes on working for transformation and not just against empire” (p. 144). Rather than living our faith to simply stand against what we see as wrong, we live our faith in order to create a world we wish to see and that we believe God desires.

Some of the final questions of this book are thought-provoking and worth good individual and corporate reflection: “Can we take a walk with Christ in our places to see the parallels between the wealth in Sephoris and the poverty in the streets and the desecration in the countryside? Will we follow a teacher that unveils the violence of extraction and exploitation that permeates our daily life, and shows us a joyful alternative?” (p. 181).

If we are willing to take this Christian walk and follow this Savior, what kind of good news might we help come alive in the world? Where are places that we can create joyful community and an alternate vision to empire? Dickinson’s exploration of parables, other scripture passages, and the Lord’s prayer makes it clear that we are to follow Jesus on paths that engage the world around us for the well-being of all.

The work of the Presbyterian Hunger Program is possible thanks to your gifts to One Great Hour of Sharing.

Cross-posted from an Eco-Journey article.

Subscribe now to the Eco-Journey Blog