By Rebecca Barnes, Coordinator, Presbyterian Hunger Program

“If we say we are without sin, we deceive ourselves, and the truth is not in us.” For many of us, this line of confession has been part of the liturgy of our worship and our lives for a long time. As Christians, we articulate a belief that we are created in the image of God and are beloved, and also that we are human, we make mistakes, and we are flawed. We get caught in personal and corporate brokenness. We do not do what we ought. We do what we ought not. This is part of our conundrum and our identity, and a reason we confess before neighbor and God.

Also critical to our tradition is our conviction that God meets our confession of sin with love and grace and mercy. We believe that the Holy Spirit can enliven and empower us to transform our lives, to turn from sin and to embrace new life offered in Christ. This grace is not cheap. It does not say that sin doesn’t matter. It doesn’t mean that we can go back in time and undo our offense. It means that we are loved in a way that allows us to start again, to begin again, this moment, to do better to open ourselves to God and allow the Spirit to work in our lives for God’s desires for a beloved community.

So why is it so hard for people of my racial background—white people—to be real about racism, white privilege, and white supremacy? Why is it really hard—and harsh to our ears—to admit that we have lived, breathed, and been taught racism and absorbed it through our bodies and brains from a very early age? Why do we have the impulse to start sentences with “I’m not racist…”? I have never heard someone proclaim “I’m not a sinner…” I can just imagine what church people would think if someone threw that claim into conversations.

Instead of proclaiming that we couldn’t possibly be associated with something hurtful, we say in church settings: I have sin, I participate (sometimes unknowingly) in sin, and I confess sin in myself and in the world around me. I am aware of the power of sin even as I believe God’s love and grace are more powerful.

What if similarly we said, I have racism inside me, I participate (sometimes unknowingly) in racism, and I confess race-based privileges for myself (a white person) and a standard/supremacy our culture has long maintained for people in my racial category (white people). I need God’s help, I invite the Spirit in, I feel Christ’s companionship as I confess the sin of racism in myself and the world around me so that I can be empowered by the Holy Spirit to undo racism and white supremacy culture?

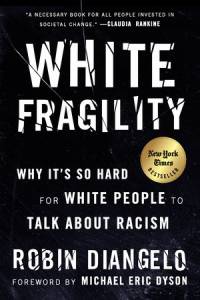

There is so much to learn from the book White Fragility*. This is just one of many learnings. Our inability to say, “I’m white, I’m privileged, I’ve been raised in a racist culture and so have we all”—should sound hollow. It should be hollow to feel so unable or uncomfortable to admit complicity, as Christians who regularly confess that we are flawed, that we have sin. It doesn’t mean that we are “bad,” on a good/bad binary, as the author talks about. There is no such thing as a sinless person, more beloved by God than the sinner. We don’t have to bend over backwards to try to prove we are a good white person as opposed to a bad white person. Instead, we need to get over ourselves, admit our complicity, and move to action for racial justice so we can get closer to becoming the kin-dom that God calls us to be. We trust our belovedness, and we trust that we can and have gotten it wrong. We ask God’s help, and we learn, and we do better.

PHP understands that ending hunger and poverty can only happen by creating just economic policies and healthy, equitable food and farming systems. We believe that dismantling systemic racism is a central component of this work.

For Racial Justice Resources visit https://www.pcusa.org/racial-justice-resources/

Tips for what allies can do from ‘Black Lives (Still) Matter’?

*Sustainable Living and Earth Care Concerns purposes to accompany Presbyterians reflecting on decisions as an extension of their faith and values. As a staff we remember our own need for faithful discipleship through continuous education, questioning and discovery. Most recently we have done that by reading the book White Fragility: Why It’s So Hard for White People To Talk About Racism. The New York Times best-selling book explores the reactions of white people when challenged around race and how these reactions maintain systems of racial inequality. See other staff reflections here and here.

The work of the Presbyterian Hunger Program is possible thanks to your gifts to One Great Hour of Sharing.