This piece is part of an ongoing series focused on the themes of “connection” and “community.” Follow the blog or check our Facebook page to see the other posts in the series as they’re published.

A month ago, in a Goodwill I found a used no-frills record player. Elina, my daughter, grabbed it before someone else stole it from her. We’ve been on the lookout for an LP player for months. As soon as we tested to see it worked at home, she threw my coat at me and said we are going record shopping.

Did you know records cost $33 dollars! At least!

Thirty three dollars gets you three months of Spotify, which gives you access to all the music you ever wanted and play it anywhere you take your phone. Any music, anywhere! But Elina wanted to hold a record in her hand, those large flat frisbee sized discs, and feel its curved edge on her palms. She wanted to see it wobble under a needle. She wanted to hold the square record cover, appreciate the Instagram dimensioned artwork, then tilt it and watch the record slip out of that sleeve lovingly into her hands.

So we went shopping.

Did I tell you that most records cost $33 dollars?!!

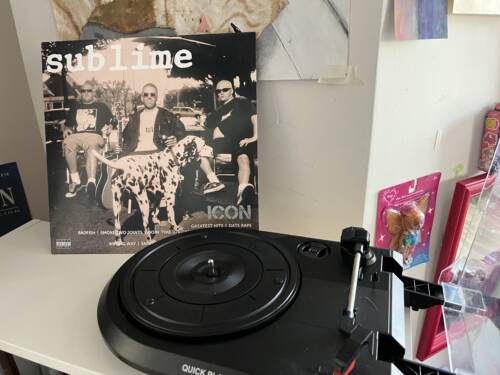

We found Sublime’s Greatest Hits. We listened to the hits I grew up on. This ska punk band had some prophetic bombs in their syncopated guitar riffs!

LP records are in a boom no one predicted. In 2022, customers bought $1.2 billion dollars of vinyl records. Since 2007, LP sales has been growing and there’s no slow down in sight. Audiophiles say that it is the warm analog sound people are ponying up for. Some, it’s a fashion trend. Nostalgia says others. But where is nostalgia for Elina who don’t have a memory of spinning vinyl music?

LP records are in a boom no one predicted. In 2022, customers bought $1.2 billion dollars of vinyl records. Since 2007, LP sales has been growing and there’s no slow down in sight. Audiophiles say that it is the warm analog sound people are ponying up for. Some, it’s a fashion trend. Nostalgia says others. But where is nostalgia for Elina who don’t have a memory of spinning vinyl music?

It’s a collective nostalgia. We humans instinctively long for days when we owned things, when we had responsibility for physical items. That teens, like my daughter, long for the old days of owning records when they do not have memories of those old days, speaks to the deep human desire to have a connection with the material world. In a world of non-things, says the philosopher Byung-Chul Han in his book titled Non-Things, we long for the grounding of things.

“We are today experiencing the transition from the age of things to the age of non-things,” because “Information, rather than things, determines the lifeworld. We no longer dwell on the earth and under the sky but on Google Earth and in the Cloud. The world is becoming increasingly intangible, cloud-like and ghostly.”

Music comes to us mostly as information. This bodiless existence has enormous perks. Music can be anywhere and everywhere all at once. That information can be played in a smart speaker and in your car. You don’t have to lug it around. It lives up there in the cloud, so it can live everywhere. But we never own it. When we pay for music service we are paying for access. We get to hear it. But it doesn’t belong to us. We stop paying, we can’t hear it again.

This lack of physicality, and thus the lack of ownership, creates a non-relationship. We don’t have a deep relationship to a song because it doesn’t relate to us in any physical way. For the price of having anywhere-access we lose relationship and accountability. In a connected world, we are increasingly more disconnected to the very things we are connected to. Our loneliness feels more empty because we are more aware of all the things we are disconnected from.

We earthly creatures need, as Han says, “the terrestrial order” by which “things that take on a permanent form and provide stable environment for dwelling.”[1] By permanence, Han doesn’t mean eternal. Permanence is a property of physical things that occupy space. Physical things don’t disappear because one does not “see” it, i.e. access it. Object permanence. A truth we learn in our development that gives us confidence in the world: “Mother hasn’t vanished. She continues to exist even when I don’t’ see her.”

Digital content is eternal (potentially) because it is ephemeral, coming in and out of existence as needed. Permanance is the physical fact that the LP record still occupies Elina’s room even when she is not hearing it. Things exist independently of our own existence. It is a “terrestrial order” that grounds us, a solid reality under our feet.

That physical property, however, makes the physical thing impermanent. Impermanent permanence. LPs can break. Elina got into a fight with her younger brother who tried to scratch the record like he saw on a youtube videos.

“Are younger brothers just born dumb!”

She can lose the record. But that permanent/impermanent nature of the physical record creates the relationship. She cares for the record because if she isn’t careful, it can be scratched, the music destroyed, gone forever. That level of care coming out of temporality creates great affection. There are multiple copies of that record, to be sure. Many others purchased the Sublime’s Greatest Hits record. But to her, the record she bought is the only record that matters. That one record is THE record because she owns it. She doesn’t have access to the music outside of that LP. She doesn’t own the music. She just owns that record. Yet, the music in that record is hers. It is a contract that Sublime and she entered into when she purchased that record.

That record will carry the history of that contract/covenant/relationship in the “grooves” of the album cover. Little dings and dents all telling a story. Her journey with that record started when she was 16. She will play it when she needs it in various emotional situations: to celebrate with her joy or to join her in her outrage. Who knows on what other journeys the record will accompany her. To her college? To her first home? Maybe even passed on to her own daughter, as she tells her daughter how Sublime put to music her angst as a teenager seeing both the beauty and ugliness of the world.

We are losing such relationship with the things of the world.

From dust we are, to dust we return, not the cloud. In dust we find our connection and being.

Marie Kondo, author of The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up and a star on Netflix, is a prophet for restoring our relationship with the material things of the world. She believes if we order our house, we can order our lives. No, she is not an organization freak. Rather she is reminding us of what Han is reminding us. We need “things,” but we need an orderly relationship to things. The solution to resist the digitization of our life into non-things, is not to buy more things, but to have a healthy (dare I say spiritual) relationship to things. Kondo invites us into a world where we are generous and respectful of things.

“When examined carefully,” she says, “the fate that links us to the things we own is quite amazing. Take just one shirt, for example. Even if it was mass-produced in a factory, that particular shirt that you bought and brought home on that particular day is unique to you. The destiny that led us to each one of our possessions is just as precious and sacred as the destiny that connected us with the people in our lives.” The mystery and miracle of all things/beings and our connections!

When she goes into a family’s home, the first thing she does is kneel and pray, thanking the home for its continuous protection. You can’t see the home the same way after you kneel. Stop reading this and try it right now!

Both the Cloud/internet and capitalism/materialism divorce us from things. The cloud takes us out of the physical world. Capitalism and materialism burden us by making more things and making us need ever more things. But here is the dirty secret in the mess of materialism: It is not that we love things too much; we don’t love them enough. We keep getting more because we don’t honor what we have. We love possessing, so we don’t know how to love what we possess. The way out of the ever-growing mass and mess of possession is to actually be more materialistic, more “thingy!” Pay attention to our things. Recognize them as beings. Or as Sublime says, “Well, life is too short, so love the one you got!”

[1] Byung-Chul Han, Non-Things: Upheaveal in the Lifeworld. Non-things: Upheaval in the Lifeworld – Byung-Chul Han – Google Books

Samuel Son is the Manager of Diversity and Reconciliation at the Presbyterian Mission Agency.

Samuel Son is the Manager of Diversity and Reconciliation at the Presbyterian Mission Agency.