You can take the pastor out of the church, but you can’t take the Church out of the pastor.

We’re all God’s children

We’re all God’s children

What I feel, as a black father, when I see a South Carolina police officer throw a teenage girl across a room

by Derrick L. Weston

Ever since my divorce and subsequent move to Baltimore, I generally see my kids twice a month. It’s not nearly enough. Over those weekends, I become an emotional camel, storing up enough of their joy and vitality to sustain me till I see them again. Like most parents, I think my children are extraordinary. They are beautiful, smart, creative, funny, and most importantly, kind. I would do anything for them, and I would do anything to ensure that they are safe and cared for.

The other day I was in the hardware store. The clerk who checked me out was a very pretty bi-racial woman, probably between the ages of 18 to 22. I’m pretty good about making eye contact with people, particular people who are helping in places like restaurants and stores. As I met this young woman’s eyes, I thought to myself, “My daughter might look like her at this age.” The moment that thought crossed my mind, I looked at her differently. I hope it didn’t come across as creepy, but I could definitely feel my expression soften. I wondered about her family, her hopes and fears, whether or not she hated her job. That moment of personal association transformed her in my mind from a random store clerk to a human, made in God’s image, deserving of love and respect.

By now, we’ve all seen and dissected the video of Officer Ben Fields’s assault on a young African American woman at Spring Valley High School in South Carolina. While this has mostly been discussed as a case of police brutality, there’s something for me as a father that I cannot overlook: I would be livid if this was my child!

‘If I slammed everyone who sassed me, I’d have the WWE championship title by now. Kids test their limits. They push their boundaries. They want to know if you’ll still be there when the smoke clears. Absolutely, young people need discipline and boundaries, but something far more nefarious is at play here.’

I’ve heard the push back: she was “sassing;” she was disrespectful. First off, the video doesn’t show her being disrespectful; secondly, who cares?! She’s a child! She’s a minor in a schoolroom. In what world is this justified? I work at a community center surrounded by kids. If I slammed everyone who “sassed” me, I’d have the WWE championship title by now. Kids test their limits. They push their boundaries. They want to know if you’ll still be there when the smoke clears. Absolutely, young people need discipline and boundaries, but something far more nefarious is at play here.

A recent New York Times article about the increase of heroin use in white communities highlights the problem for me.

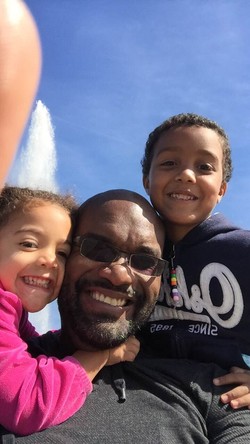

Derrick Weston with his children

“When the nation’s long-running war against drugs was defined by the crack epidemic and based in poor, predominantly black urban areas, the public response was defined by zero tolerance and stiff prison sentences,” writes Katherine O. Seelye. “But today’s heroin crisis is different. . . . And the growing army of families of those lost to heroin—many of them in the suburbs and small towns—are now using their influence, anger and grief to cushion the country’s approach to drugs, from altering the language around addiction to prodding government to treat it not as a crime, but as a disease.”

To me there is both something tragic and incredibly hopeful about this. The tragic piece is that there was, and still is, an undervaluing of lives based on race and economics. The hopeful piece is that something that was once an isolated pain is becoming a pain held in common. When “your” problems become “our” problems, we can begin the long trek towards solutions and healing. Perhaps we even come to understand what Paul meant when he described the one body of Christ, whose members suffer collectively when even one part suffers (1 Cor. 12).

I’ve spent a lot of my career doing youth ministry. I often think about returning to that work. I’ve had the great privilege of speaking to large numbers of youth over the years at places such as the Montreat Middle School Conference and Mo-Ranch. There is something life-giving and life-affirming that comes with investing in young people. While my work now isn’t youth ministry strictly speaking, there are young people running in and out of the community center where I work all the time. I love being “Mr. Derrick” to them. I love that they know that they will be safe and respected here. In a very real way, they too are my kids.

“We’re all God’s children” is the common platitude I hear in discussions about inequality when people don’t want to deal honestly with the realities. While it is not a false statement, and while it can in fact be a radical statement, it is one that demands to be treated much more seriously than as a way of dismissing dialogue about the real differences of treatment, access, and privilege. We are all God’s children, and that’s why these inequities are unacceptable. If we do deeply believe that we are all reflections of the divine image, then we should be working to make sure that all “our” kids receive love, not violence.