Public memorial service to be held on June 10 at 2 p.m. at KFC YUM! Center, adjacent to Presbyterian Center

by David Gibson | Religion News Service. Additional reporting by Emily Enders Odom | Presbyterian News Service

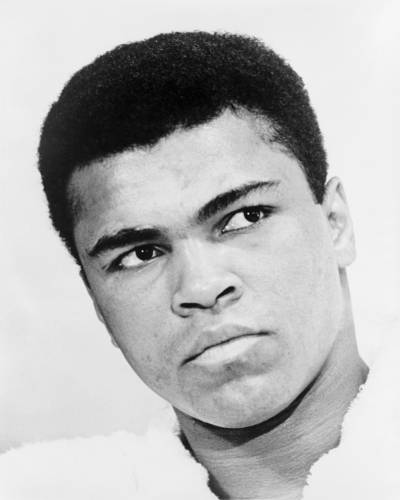

LOUISVILLE – As a grieving city, nation, and world respond to the death on June 3 of Muhammad Ali—the larger-than-life boxing champion, poet, and humanitarian—the Rev. Dr. Charles Wiley III, coordinator for the Presbyterian Mission Agency’s office of Theology and Worship remembered Ali “as bombastic, an enormous talent, and someone who stood up for what he believed in.”

“Ali’s conversion to Islam and refusal to fight in the Vietnam War made him deeply unpopular among many in the United States, yet he matured into a man who broke down barriers as he introduced countless citizens to Islam,” Wiley said. “His commitment to peace and understanding in his later years stands in contrast to his early persona, but he, like all of us, lived a more complicated life than can be summarized in a headline.”

Ali was born in Louisville, Ky., on Jan. 1 7, 1942, as Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr., a name shared with a 19th-century abolitionist. His father, a billboard painter, was a Methodist but allowed Clay’s mother, who worked as a domestic, to raise their children as Baptists.

7, 1942, as Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr., a name shared with a 19th-century abolitionist. His father, a billboard painter, was a Methodist but allowed Clay’s mother, who worked as a domestic, to raise their children as Baptists.

Young Cassius Clay was introduced to boxing when he was 12, and was so extraordinarily gifted that through his teenage years he amassed numerous amateur titles, culminating with a gold medal in the light heavyweight category in the Rome Summer Olympics in 1960.

But Ali, always a headstrong and often brash personality, was fast becoming aware of the racial inequities of his sport. “Boxing is a lot of white men watching two black men beat each other up,” as he put it in one of his many memorable lines.

He saw the same dynamic, and restiveness, in American society. While he gained fame as a professional boxer in the early 1960s he also gravitated toward the more fiery voices speaking out on behalf of African-Americans.

One of those was Malcolm X, who was key in introducing Clay to the Nation of Islam, a group that was founded in Detroit in the 1930s as an amalgam of Islamic teachings and messianic claims.

[His conversion] came at a cost to Ali. The World Boxing Association barred Ali after his conversion. Three years later, when Ali was drafted to fight in the Vietnam War he cited his beliefs as the basis for his refusal to serve, and that would lead to a total exile from the sport.

“My conscience won’t let me go shoot my brother, or some darker people, or some poor hungry people in the mud for big powerful America,” as he put it. “And shoot them for what? They never called me nigger, they never lynched me, they didn’t put no dogs on me, they didn’t rob me of my nationality, rape or kill my mother and father. … How can I shoot them poor people? Just take me to jail.”

Ali was convicted of draft evasion in June 1967 and sentenced to five years in prison. He remained out on bond while he appealed, but he was barred from all boxing, from the age of 25 to almost 29 — his prime.

Yet those years also saw the beginning of a sea change in American attitudes about the war, and the implementation of landmark civil rights laws. Ali was no longer the outlier he had once been.

Lines wrapped around the YUM Center block on Wednesday to get tickets for Muhammad Ali’s funeral service on Friday. Photo by Rick Jones.

He was able to begin boxing again in 1970, and a year later, the U.S. Supreme Court overturned his draft evasion conviction in a unanimous ruling.

As Ali started re-establishing his reputation as a brilliant and fearsome fighter, he also continued to speak out against racism, war and religious intolerance. All the while, he projected an unshakeable confidence and humor that became a model for African-Americans.

“Ali advanced something that Presbyterians seek to do: to break down the barriers between people of different faiths to work together for peace and justice,” Wiley said.

Quoting the “The Interreligious Stance of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.),” a policy statement adopted by 221st General Assembly (2014), Wiley added, “Presbyterians see these interreligious relationships ‘as a specific instance of Christ’s universal command to ‘… love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind’ and to ‘love your neighbor as yourself’ (Mt. 22:37, 39).”

![]() You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.

You may freely reuse and distribute this article in its entirety for non-commercial purposes in any medium. Please include author attribution, photography credits, and a link to the original article. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDeratives 4.0 International License.

Categories: Ecumenical & Interfaith, Faith & Worship

Tags: civil rights, interfaith, muhammad ali, peace

Ministries: Interfaith Relations