Comments from Andrew Kang Bartlett, Presbyterian Hunger Program, at the Spirit of the Harvest Festival on October 20, 2016 in Sebastopol, CA, sponsored by the Interfaith Sustainable Food Collaborative

Comments from Andrew Kang Bartlett, Presbyterian Hunger Program, at the Spirit of the Harvest Festival on October 20, 2016 in Sebastopol, CA, sponsored by the Interfaith Sustainable Food Collaborative

“It’s an honor to be with you. And it’s great to be here in California where I lived for 13 years before moving to Louisville KY in 2001. I don’t do much public speaking, but I would like to share some words with you.

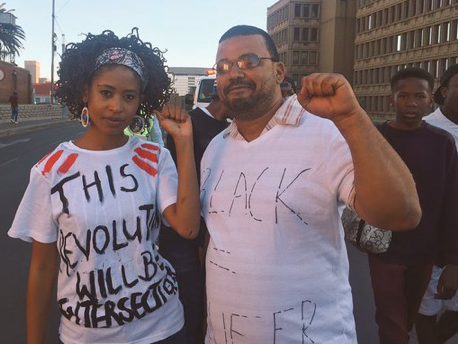

I just left the farmworkers in Washington state and I have an update, but I’d first like to talk about intersectionality and revolution. Last week, my colleague at the Presbyterian Hunger Program, Jennifer, a young African-American mom, wore a T-shirt to work.

Jennifer is shy so I didn’t get a picture of it, but similar to this one it said:

Jennifer is shy so I didn’t get a picture of it, but similar to this one it said:

“The Revolution Will Be Intersectional.”

What does this mean to you? What does this mean to us in 2016?

“The Revolution Will Be Intersectional.”

Can I see a show of hands? Raise your hand if you’ve heard the term intersectionality in the last year?

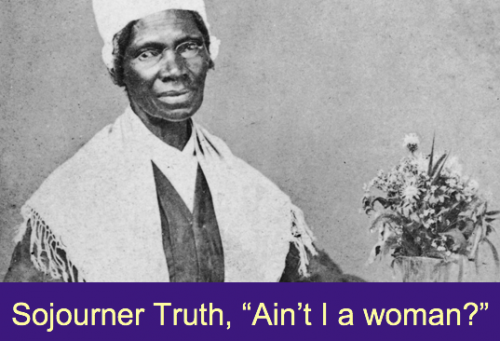

The concept of intersectionality goes way back, and certainly as far back as Sojourner Truth’s famous speech in 1851 “Ain’t I a Woman?.” But intersectional as a word was first coined in 1989 by Kimberlé Crenshaw.

The concept of intersectionality goes way back, and certainly as far back as Sojourner Truth’s famous speech in 1851 “Ain’t I a Woman?.” But intersectional as a word was first coined in 1989 by Kimberlé Crenshaw.

Crenshaw and others used this idea of intersectionality as a foundational linchpin for revisionist feminist theory, which looked at the intersection of gender and color, in particular how black women were discriminated against in ways that were unique because of dual or multiple identities. Intersectional thinkers recognized that the forms of oppression experienced by white middle-class women were different from those experienced by black, poor, or disabled women.

Simply put, when aspects of an individual or a people’s identity is not considered, they will not be fully understood, AND the full array of obstacles they face will not be addressed.

The Revolution Will Be  Intersectional…Often added to this — or It Won’t Be My Revolution

Intersectional…Often added to this — or It Won’t Be My Revolution

Firstly, we will be having a revolution. Given our unsustainable and often cruelly unjust systems, it is coming and it will be either reactive and violent, or it will be fomented by great organizing, alliance building and people power. But “it won’t be my revolution” if it is single focused – on violence or on race or on class alone – and it fails to recognize the fullness of who I am.

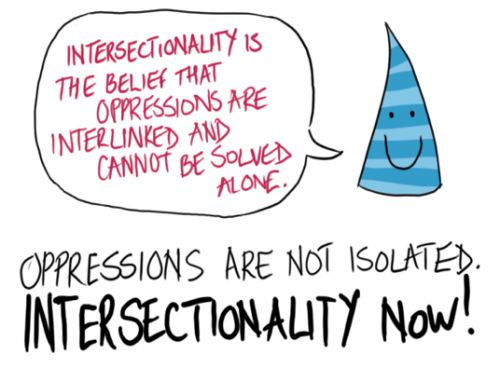

Today, intersectionality has become a popular term, perhaps especially among feminists and LGBTQ people of color. As I understand it, what this means is that oppression is holistic. Oppressions within society, such as racism, sexism, classism, ableism, homophobia, , xenophobia and bigotry—do not act independently of each other. Instead, these forms of oppression interrelate and create a system of oppression that reflects the “intersection” of multiple forms of discrimination.

Why does that matter? Because when we look around, black and brown men and women, the mentally disturbed, gay and trans people, and other non-white, non-straight, non-male people are locked up, dying young, and are being killed in the streets of modern day America. These deaths and the racist, anti-immigrant, xenophobic rhetoric gushing from the mouths of certain candidates and politicians remind us that racism and other isms are alive and well in the behavior of hateful people and in the subconscious thoughts of well-intentioned people like you and me. Then on top of this, we are facing huge economic, environmental and climate crises all at the same time.

Given all this, it takes real courage to pull ourselves away from Netflix series and kitten videos and to live out what it means to be a person of faith. Believe me, I know this from personal experience. The problems are so big, … and not only must we change the systems themselves, but we know we must change the thinking that created the systems. Starting with you and me, we must unshackle our minds.

Fortunately, our Abrahamic faiths are all about liberation. We are instructed to break the yoke of oppression!

As Christians, Jews, and Muslims, we are in the freedom business. It all comes down to liberation, because until you are free, I cannot be free. And until we are all free, we can never love as Jesus loved.

Unconditional love is our destination. On earth as it is in heaven. With love as our destination, our journey is fueled by liberation. Liberation from fear. Liberation from want. Liberation from injustice and exploitation. Liberation from greed and prejudice. Liberation from a fallacious world view of me versus other, of us versus them, of human versus nature. The freedom to unconditionally love self, neighbor and God.

While the term isn’t 2000 years old, I would contend that the ministry of Jesus Christ was intersectional. Intersectionality would come naturally to a man of his social position – chased from the day he was born by a king who wanted him dead, conceived to an unmarried young mother, born in a stable in Nazareth of all places.

To paraphrase the actor John Fugelsang – Jesus was a radical, nonviolent revolutionary who hung around with lepers, prostitutes, and crooks. He wasn’t American, didn’t speak English; was anti-wealth, anti-death penalty, anti-public prayer (Matthew 6:5); he never called the poor lazy, never justified torture, never fought for tax cuts for the wealthiest Nazarenes, never asked a leper for a copay; and was a long-haired brown-skinned homeless community-organizing Middle Eastern Jew.

In his stories, throughout his life, and in who he chose as companions and fellow leaders, Jesus intentionally included orphans, Samaritans, widows, disabled persons, the criminal he was crucified with, and of course the poor.

- Following the footsteps of Christ, our path to love through liberation must be intersectional.

- We must see and understand the complex identities of persons and communities of people.

- We must know them, feel them, put ourselves in their skin, see through their eyes – because ultimately they are our eyes.

- We must offer our unique gifts, our talents, our treasure and our spirit.

- We must be embraced by each other and move as one.

What might this look like in the coming week, months and year for you? What are the opportunities to do this in your own community?

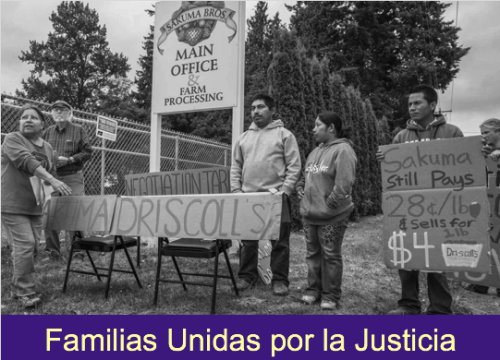

Here’s what it looked like in Washington state. Grassroots leaders and members of Familias Unidas por la Justicia understood that their struggle needed intersectional solidarity. For years, they have been struggling for respect, better conditions and fair wages. When people heard their story, many agreed that an injustice anywhere was an injustice everywhere.

These farmworkers in Washington are indigenous peoples from southern Mexico. They are among the most vulnerable and exploited people in our country, and yet they also believe in the power of people working together.

They work on the Sakuma Brothers Farms and pick berries for Driscoll, the largest berry distribution company in the world. To succeed, they knew their demands must find resonance among other farmworkers, other immigrants, students, people of faith, and farmworker allies – like the ordained Presbyterian, Sam Trickey, on the left side of the photo, with whom I serve on the National Farm Worker Ministry board.

Familias Unidas worked for years to form a union that would be recognized by Sakuma Brothers and to negotiate a binding contract. They called for a boycott and people around the country joined in. Berry pickers in San Quentin Mexico also joined in calling for a boycott of Driscoll and they continue to do so.

But in Washington, Sakuma has agreed to recognize them as a union and negotiate a fair contract. They have won.

All along the way, they had the support of Community2 Community, a farmworker cooperative and advocacy group led by Rosalinda Guillen (on the far left), who was with us in Seattle. Rosalinda explained what this victory means.

All along the way, they had the support of Community2 Community, a farmworker cooperative and advocacy group led by Rosalinda Guillen (on the far left), who was with us in Seattle. Rosalinda explained what this victory means.

She said, “This is the end of the road for them. There’s no place else to go. Workers won this election because they know what they want. They have families here, and are looking for a better future for their kids. It’s not a temporary job for them. They’re part of this community.”

Felimon Pineda, the vice-president of Familias Unidas added, “We are all part of a movement of indigenous people. In San Quentin, the majority of people are indigenous, and speak Mixteco, Zapoteco, Triqui, and Nahuatl. … Everyone involved in our union in Washington is indigenous also.”

“No matter if you’re from Guatemala or Honduras, Chiapas or Guerrero – the right to be human is for everyone,” Pineda added. “But sometimes people see us as being very low. They think we have no rights. They’re wrong. The right to be human is the same. There should be respect for all.”

The Presbyterian Hunger Program is one of the founding members of the US Food Sovereignty Alliance. In 2014, we gave the Food Sovereignty Prize to Rosalinda’s group, Community2Community. On Saturday, we gave the 2016 Food Sovereignty Prize to the Alliance for Food Sovereignty in Africa and to the Farmworker Association of Florida.

The US Food Sovereignty Alliance, along with the many movement-building groups and coalitions that the Presbyterian Hunger Program supports, base their work on intersectionality and on collective work towards liberation. Hopefully you have found groups like that to work with. If not, seek them out and join in their work – because if this revolution of love is to happen, it will be because each of us does our part.

In closing, I will leave you with the words of Lilla Watson, an indigenous Gangulu woman from Australia. They are words of caution and inspiration.

“If you have come here to help me, you are wasting your time. But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together.”