Reforming our churches:

Becoming intercultural communities

From “Chosen People-Promised Land Model” to expansive covenant

by Andrew Davis

When I think of multicultural churches, I do not necessarily think of my own — I picture congregations that reflect many different races and ethnicities. Like most PC(USA) churches, Union Presbyterian Church of Saint Peter, Minnesota, is a predominantly white congregation. What does multicultural ministry mean for my rural, Midwestern church community?

I believe it first entails shifting from a “Chosen People–Promised Land Model”1 to a sense that being the church is about including everyone within God’s expansive covenant. Union was founded by missionaries whose methods of evangelism were based on conversion techniques typical to the 19th century. The emphasis was on denying all aspects of one’s birth culture in order to convert to the traditions of Western European Christianity. Many of the Sioux understandably resisted such attempts at colonialism and conversion. The Rev. Stephen Riggs, a founder of the church that would become Union, noted, “Preaching seems like pouring water upon a rock.” Subsequent military and governmental injustices culminated in the U.S.–Dakota War of 1862 and the removal of remaining Sioux peoples from their lands in south-central Minnesota. I know this history because church members compiled a book about Union for its 150th anniversary. Telling the truth about our own history is an important first step in working for racial justice.

Union became a mostly white church in a mostly white city because of this unjust theology of domination. Truly, it is by the grace of God that we have been moved to a new paradigm for ministry. Today, Saint Peter is becoming more diverse. Thanks to good wages and a low cost of living, refugees from Somalia are choosing to make this land their home. These Somalis are Muslim; they worship in a small mosque in town. It would be “like pouring water upon a rock” a second time to try to convert them to Christianity. Instead of a theology of domination, Christians in Saint Peter are embracing a theology of what I call “expansive covenant.”

In the Hebrew scriptures, covenants delineate the neighborly duties and responsibilities of people to each other and to God. Biblical laws set forth how God should be worshiped and how God’s people should treat one another. However, peoples outside the covenant (such as Samaritans) were not given the same neighborly designation. Shockingly for the Jews, Jesus taught that the essential terms of the Jewish covenant could be fulfilled by non-Jews. In the parable of the good Samaritan (Luke 10:25–37) and in the story about the Samaritan whose leprosy was cured (Luke 17:11–19), Jesus provided examples of Gentiles who loved God and who loved their neighbor as themselves, thus fulfilling the greatest commandments of the Jewish covenant (Luke 10:27). In Jesus’s teachings and through the movement of the Holy Spirit, Gentiles were graced with the benefits of the covenantal relationship with God and neighbor, even though they worshiped God in their own, different ways. Likewise, Christians can recognize the Muslims who recently moved to Saint Peter as being in a covenantal relationship with God, even as they worship and think about God in distinct ways. We are obliged to love with the same love that God offers us in Jesus Christ. Love, not domination, is at the center of a multicultural theology of expansive covenant.

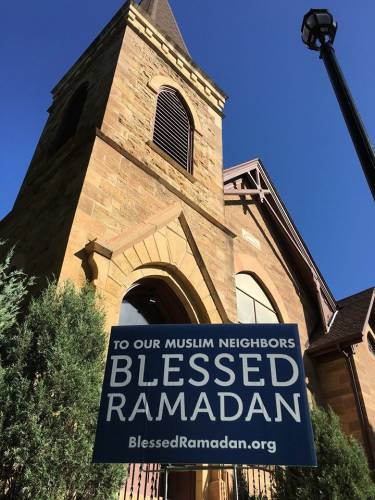

Another aspect of covenantal theology is that it concerns public goods. In ancient Israel, the terms of the covenant described the ordering of public life and property. For example, in Deuteronomy 19:14, the law prohibits the movement of a neighbor’s property boundary. Although our modern and secular democracy is radically different than the theocratic monarchy of ancient Israel, we can still use covenantal theology’s concerns for public order to the good of our communities. In a secular democracy, public goods are available to all, regardless of religious affiliation. As Christians operating within a secular democracy, though, we recognize the value of religion, and we can work to ensure that the public order protects the right to religious assembly for all. I’ve had some success in helping to protect religious assembly in Saint Peter by joining and then chairing the Planning & Zoning (P & Z) Commission, which operates under the authority of the Saint Peter City Council. Zoning laws regulate land use, and the P & Z decides whether an applicant for a zoning variance can move forward. In many cities, new places of worship require a zoning variance. I was happy to chair the meeting when our Somali neighbors applied for such a variance for their new mosque. The meeting went well, with no pushback from neighbors, but some cities have experienced attempts to block zoning variances for mosques. To prevent possible obstructions from occurring in the future, the P & Z changed Saint Peter’s zoning regulations so that fewer new houses of worship would need to apply for a zoning variance in order to build. The Christian witness to God’s expansive covenant can move us to act, even in seemingly mundane city meetings! In addition to my work on the P & Z, I have been involved as our Habitat for Humanity chapter has made it easier for Muslims to apply for mortgages, I’ve posted “Blessed Ramadan” yard signs around town, and our church has gathered mittens, scarves, and socks to help keep our neighbors warm during their first Minnesota winters. Working with the Episcopal church in town, we are developing casual friendships with families at the local Laundromat, and a community-based “Tapestry Project” set to launch in early 2020 will strive to deepen relationships between our church members and refugees.

My heart despairs at the grave injustices inflicted on the Sioux peoples by the settlers who also established my dear church. If only they had sought to be loving neighbors instead of colonizers! Now, in this time, I hope we can be faithful to the expansive Gospel of Jesus Christ in all that we do.

The Rev. Andrew Davis is pastor of Union Presbyterian Church in Saint Peter, Minnesota.

—

- Steven T. Newcomb, Pagans in the Promised Land: Decoding the Doctrine of Christian Discovery(Fulcrum, 2008).