Pilgrims, turkey and kimchi

Thanksgiving is an immigration story

by Samuel Son

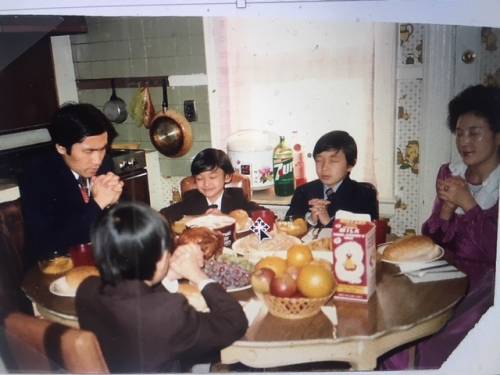

Author Samuel Son, the little boy with his back to the picture, remembers his first Thanksgiving after his family moved to the United States from Korea.

A year ago, I was going through my parents’ photo album to put together a digital slideshow for my mother’s 70th birthday bash. That’s when I happened upon this photo.

This was our first thanksgiving in America. As you can tell from the photo, it was American through and through, from the 10-pound turkey in the center, to the basket of fruits stocked to teetering height. However, there is no kimchee (pickled cabbage) at this table. My youngest brother’s face is all smiles. Next to him is my younger brother, Daniel. Even at that age he was the most pious: Note the deep furrow creasing his youthful skin around his tightly closed eyes, proof of spiritual sincerity. He is a pastor today and the church he planted several years ago is keeping him busy. My mother’s fingers are not interlocked, but folded across each other, giving her posture more “femininity.”

My father is at the head of the table. He came to New York a year before us, so at the time of this picture it was his second year in the United States. He worked several jobs and saved enough money to get a rental in a fourth floor, walk up apartment. This was not his first Thanksgiving, but the first as a family in America. He was thankful to God for that blessing because he worked hard for it.

That leaves the boy with his back to the camera. That is me. I would like to say that I was in deep prayer like Daniel. Honestly, though, I have no idea.

While this photo fills out the details, I’ve never forgotten that meal. I remember that we all felt as if we were being initiated into the American community. After all, rituals mark membership.

And what ritual is more American than Thanksgiving?

Baseball and weekly visits to Kentucky Fried Chicken assimilated us to the daily habits of Americans, but this ritual was worth a photo shoot. This holiday, my father told us around the table, embodied the core values of America: faith, hard work, family and God.

We agreed as we started pulling the meat off the turkey. We missed aunts and uncles we left in Korea, but we had the nuclear family and it felt complete. We never had turkey before this meal, not as this unsliced whole. It’s hugeness impressed us. For me, the turkey symbolized America too — its vastness, its endless stretch of land, the cavernous Coke serving cups, the width of streets, the height of its people, and their appetites. You don’t eat a chicken on Thanksgiving. You go for the largest bird you can find. So my brothers and I, as soon as the prayer and the story of Thanksgiving ended, fought for the privilege of yanking off the enormous turkey legs. There were only two of them but three of us.

The detail in the photo that always gives me a chuckle is my mother’s attire. Did she purposefully dress similar to that of a pilgrim with a large white collar? Did my mother search for that dress at Macy’s because she did see herself like a pilgrim?

Like them, she move permanently to a land they never saw, but only heard of. And in the 80’s, she left Korea believing she would never have the economic freedom to come back. Like the hard working pilgrim ladies who plowed land and lifted lumber as good as any men, my mom worked two job, leaving us children to come home from school to an empty home with snacks prepared on a table. For her, the Thanksgiving story was an immigration story.

Perhaps this was why as a family we preferred Thanksgiving over Independence Day. They story of pilgrims coming from abroad gave us a way into the American narrative fabric. We knew firsthand the sacrifice necessary for an immigrant, the immense work required to start a new life in a foreign soil, and the severe limits of hard work in a new context and your dependency on the wisdom and expertise of those who live in the new land.

To be an immigrant is to work like everything depended on you and to know that you are absolutely dependent. To make it on your own, you can’t do it on your own. We had lot of help those first few years, like the person who gave a 70’s Ford car to my father, and my mother’s sister and brother-in-law, who let us stay in their apartment for six months, their whole family voluntarily scaling back into a single bedroom so our family of five can have their second bedroom. I’m sure they also helped with the spread of our first Thanksgiving meal. In fact, the one who took the picture was my cousin, the who gave up his room as a teenager so we can crash until we can got our own place.

But this immigration story is forgotten — or too speedily glossed over — in the ritual of Thanksgiving. Like many rituals, the practice takes over until the story undergirding the practices is lost. We do things without knowing why, only that it has always been done that way. Did you know that no turkey was present in the first thanksgiving meal? But after years of turkey at Thanksgiving celebrations, you end up thinking the most important thing about the holiday is how to make the turkey juicy while fully cooked.

But Thanksgiving, as I am remembering our first such meal with you, can be a place of radical re-visioning. That is, if we remember its roots. Thanksgiving is so perfunctory and “ritualistic” that one can say the words of thanks without ever realizing that it is an admission of utter interdependence that shatters the myth of picking yourself up by your own bootstrap. Or that when we say Thanksgiving is an American holiday, we are saying that an American is an immigrant, that we came to a land not our own, and that our survival of a harsh winter was due to the kindness of those who stewarded this land for thousands of years.

If we remember that Thanksgiving is really a story of immigration, then our understanding of American identity would be a more inclusive one.

In Deuteronomy, Moses codifies a phrase every Israelite is to tell their children so they can tell their children, “A wandering Aramean was my ancestor” (Deut. 26:5). They were to remember that they were wanderers, voyagers, immigrants, lest by the amnesia of time, they forget and begin believing that the land belonged to them by right.

An American Thanksgiving is a celebration, and not just remembrance, that we were refugees and immigrants. It celebrates the bravery and the precariousness of the immigrant. Thanksgiving is a celebration of those who left the known for the unknown, chose the threat of ocean storms and new winters in a new land.

Thanksgiving celebrates generosity; that when they came, they were kindly taught how to befriend the new soil. And then in 1621, with some fowls and deer meat (no turkeys please), the natives and the immigrants shared a meal and became a family.

To celebrate that the first Americans were refugees and immigrants is to say that today’s brave refugees and immigrants — battling the odds to make it to a land that was never ours to claim — are also Americans.

Samuel Son is a manger of diversity and reconciliation of the Presbyterian Mission Agency.